By Lura Roti for AgSpire

There are three things the most profitable cattle producers do:

- Wean the highest percentage of exposed cows

- Wean the heaviest calves

- Never skimp on bulls

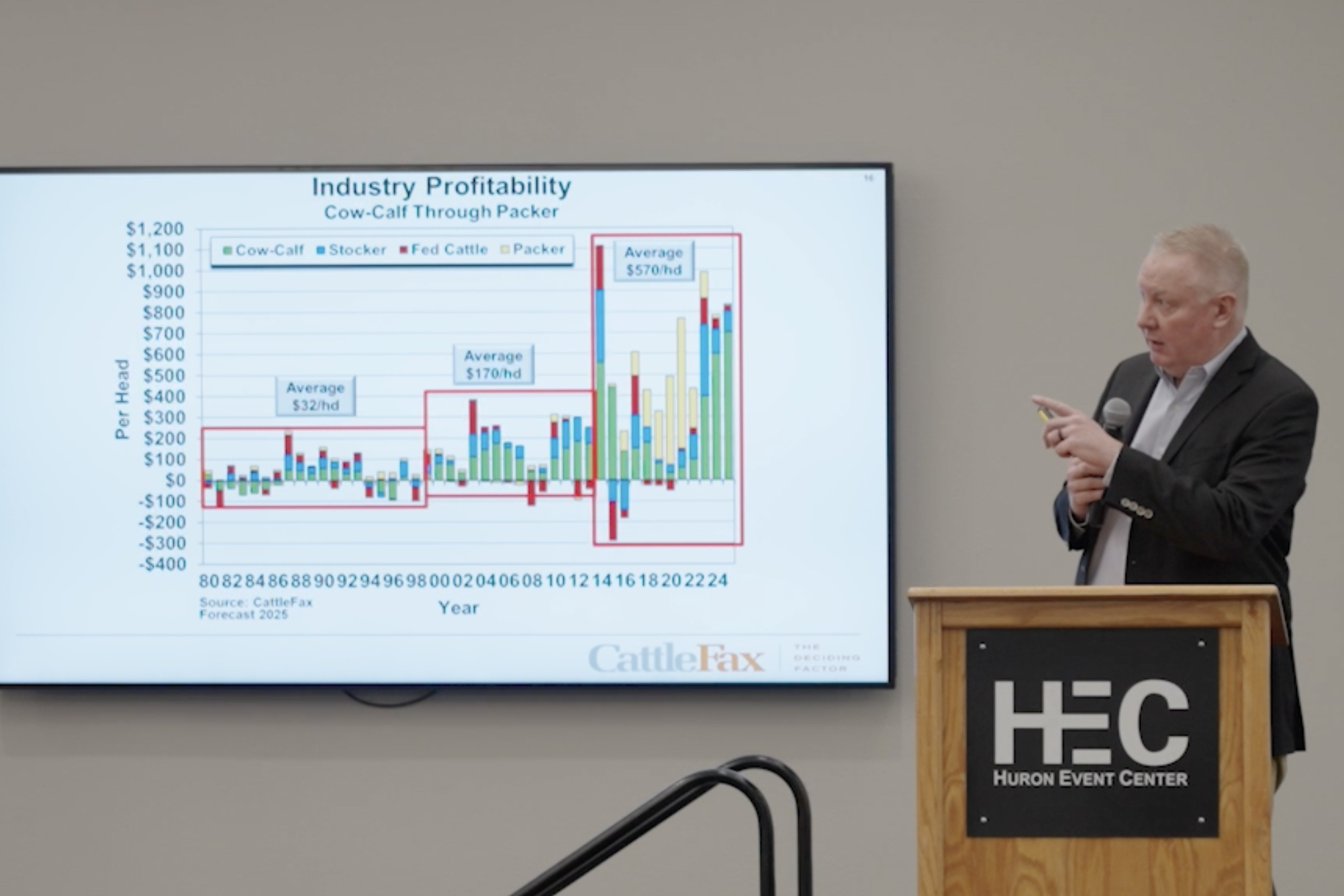

This data was collected from CattleFax surveys of nearly 20,000 cattle producers. And it was shared with South Dakota cattle producers by Mike Miller the Chief Operating Officer of CattleFax, the world’s leading beef industry research and analysis firm during the Ranching Resilience workshop hosted in Huron, S.D., by AgSpire this February.

“So, to recap, they are paying very close attention to their genetics. They are taking care of the calves that hit the ground. And they are doing their darndest to make sure that when it’s all said and done, they’re selling the most pounds,” Miller explained. “And for those of us who have room to graze or grow cattle, there is money in that segment of the industry each and every year.”

For those of us who have room to graze or grow cattle, there is money in that segment of the industry each and every year.

Mike Miller, CattleFAXIn addition to sharing the survey findings, Miller presented an in-depth market outlook.

Miller’s message resonated with Greg Hofer, a fourth-generation Hitchcock cattle producer. “You are never too old to learn something new. That’s why we attend these workshops, to bring new ideas home to our operation,” said Hofer, 65, who attended the workshop with his son, Dwight.

New information matters to Hofer because of the next generation. He and his wife, Lisa, raise crops and cattle with his dad, Eldon, their sons, Ethan and Dwight, and their grandchildren.

“There have always been four generations on this farm since I was born,” Hofer said. “We are not a large operation, but we are large enough for everyone to be involved if they want to be.”

Cattle operations like the Hofer’s are the reason AgSpire invited nationally renowned experts to Huron, explained Jared Knock, a cattle producer and AgSpire’s Vice President of Agriculture Innovation.

“Over the last several decades, the cow herd has taken secondary position of priority behind crop farming, and our landscape reflects this,” Knock said. “With this workshop we wanted to bring some of the best experts in the country to provide cattle producers with long-term forecasting on the state of the beef industry and provide them with research-based advice on how to increase their operation’s resiliency moving forward.”

To provide cattle producers with research-based information to maximize resilience through herd efficiencies, grazing and ultimately profits, Miller was joined by Cliff Lamb, reproductive physiologist and Texas A&M director of AgriLife Research and Justin Fruechte, ag product expert for Renovo Seed.

Improved herd efficiencies help produce more food on less land

Increasing production efficiencies to produce more products and profit on less land is an overarching focus for Lamb in his role with AgriLife Research.

“We focus on sustainable production systems. And it’s not just environmental, its economic …because you cannot have a sustainable system if you don’t have economic viability,” Lamb said.

And when it comes to increasing herd efficiency, Lamb said of all the genetic traits cattle producers select for, research shows pregnancy has the greatest impact on profits.

“Pregnancy is the number one trait beef producers should be thinking about,” Lamb said. “Pregnancy is about four times more economically important than any other production trait.”

Lamb shared additional research that showed heifers that get pregnant in the first 21 days of breeding season maintain their fertility longer – producing the equivalent of three quarters of a calf more in their lifetime than heifers that became pregnant the second half of a 42-day breeding season.

“Whatever you can do to figure out ways to get more cattle pregnant early on is extremely important,” Lamb said.

Some recommendations Lamb shared based on research trials were:

- Reduce breeding season to about 62 days

- Implement synchronization and AI to help reduce the length of breeding season

- Reduce heat stress during breeding season

In addition to breeding season efficiencies, Lamb also discussed research-based technologies and genomic testing to improve feed efficiencies.

Financial incentives & market premiums available to sustainability-focused producers

Herd efficiency not only matters to researchers and producers, but it also matters to major beef purchasers like McDonalds. And they are willing to offer incentives to cattle producers working to improve efficiencies because they have a vested interest in a sustainable U.S. beef supply, explained veterinarian Kristina Porter, AgSpire’s herd management technical advisor.

“McDonalds is interested in having a strong, robust beef supply domestically. That’s in their best interest. That’s in your best interest. So, they have some money set aside because they believe in what you are doing,” said Porter, referencing the Ranching for the Future program.

Ranching for the Future is one of several sustainability-focused incentive programs cattle and crop producers can sign up for through AgSpire.

AgSpire was founded in South Dakota in 2021. It is a national company that provides technical expertise, educational resources, and access to practical incentive programs to help producers succeed with regenerative and conservation practices.

“There are all these buzzwords with sustainability, efficiency, resiliency that have gotten very popular over the years. But these are the things you all have been doing your entire career,” Porter said.

Healing the Land for Better Forage

“It is good to see that companies are wanting to endorse beef production and not just say they don’t think it is good for the environment,” said Michael Mendel, a fourth-generation cattle producer who manages his family’s cow/calf herd near Carpenter, S.D.

It is good to see that companies are wanting to endorse beef production and not just say they don’t think it is good for the environment.

M. Mendel, Event Attendee.Because he implements rotational grazing, Mendel had a particular alkali patch in mind when he listened to Fruechte’s forage and grazing presentation.

“They talked about correcting saline areas with grasses and using it for hay or a grazing opportunity. It would be such a better use of land than trying to plant and nothing gets produced,” Mendel said. “I am always looking for areas that are not making money farming, that we can plant to grass for grazing.”

Fruechte has been helping operations to heal up saline and sodic soils for more than a decade. “With the right mix of perennials, you can fix that water cycle and your saline areas will stop spreading because you’ve got a water cycle improvement and you’ve got the roots structure that’s going to allow for needed drainage.”

The ag product expert for Renovo Seed also encouraged cattle producers to consider mixing grass species with new alfalfa seedings as another way to improve soil health and enhancing forage opportunities. “When you take that alfalfa off, you start to realize just how much exposed soil there is – whether saline soil or not – I highly recommend people plant grass in the alfalfa mix.”

During his presentation, Fruechte shared the benefits of different plant species and their role in maximizing grazing, forage production and overall soil health.

Virtual Event Recording

Cattle producers who were not able to attend the February 18 Ranching Resilience Workshop can watch video recordings of Fruechte, Lamb and Miller’s presentations. Fill out the form here to get access to the event recording.